Late modernist children’s literature in the Nordic region is vigorous, colourful, and diverse – not least with the regards to the treatment of gender. Today, the notion of rigid categories concerning genre, modes of expression, medium, life periods, and gender identity has been replaced by a broader perspective, in which gradual transitions, exceptions, and particularities come into play. The present article offers a brief presentation of general trends in children’s literature before subjecting children’s literature in the Nordic countries to a feminist gaze, combining genre perspective and an emphasis on some of the most prominent female writers and illustrators.

In children’s literature, the written word has been privileged. However, in recent years Nordic children’s literature has increasingly incorporated illustrations where the written word and images have – artistically speaking – been mutually beneficial. Additionally, graphic novels and picture books aimed at an adolescent readership have been published. Many female creators of comic strips focus on the lives of girls and women, and fantasy and YA, or young adult novels present significant and innovative alternative takes on gender identity. As genres are blended, there is an emergence of debates about the relationship between genre, medium, and gender. Concurrently, new crossover categories such as tween literature and YA literature, i.e. fiction aimed at a slightly older readership than adolescents, has appeared.

There is a backdrop of distinguished writers to contemporary Nordic children’s literature: Finnish-Swedish Tove Jansson (1914-2001) is a central figure in the development of a budding gender perspective, e.g. the design of the diverse universe of the Moominvalley where Jansson also subverts the naturalisation of gender stereotypes (Witt-Brattström; 1993). Karin Michaëlis (1872-1950) and Estrid Ott (1900-1967) are early Danish examples of female writers presenting strong, independent girls’ characters with itchy feet. The Swedish writer, Astrid Lindgren (1907-2002), has played an incomparable role by creating anti-authoritarian characters such as Pippi and Emil, who consistently break social norms, and through her advocacy work for children’s rights. Among writers of the following generation, Danish Cecil Bødker (b. 1927) and Swedish Maria Gripe (1923-2007), are central representatives of a new language-oriented, modernist style introduced during the mid-1960s. (Ebba Witt-Brattström: “ Nummulitens hämnd. Tove Jansson”. Ur könets mörker. Litteraturanalyser av Ebba Witt-Brattström. Nordstedts, 1993)

Children’s Literature as Gender Laboratory

In the Swedish edition of Nordisk kvinnolitteraturhistoria (1997; The History of Nordic Women’s Literature), Nordic children’s literature is described under the title “Dialog i könsdemokratins tecken” (“Dialogue in the Name of Gender Democracy”). The writers of the article first discuss novels for adolescents, including detours to children’s books, while the picture book is conspicuously absent. While the terms, ‘dialogue’ and ‘gender democracy’, are still keywords in debates concerning the representation of gender in postmillennial children’s literature, the dialogue has changed, particularly in terms of literary modes of expression, and today, it would be inconceivable to disregard picture books and graphic novels from studies of female, feminist writers in the Nordic countries.

Male and female writers focussing on gender or publishing feminist works are pervasive in contemporary children’s literature, and women publish within all genres and categories. Illustrated books, for example, emphasise the emotions of the small child while also examining parenthood and power structures, e.g. Stina Wirsén’s (b. 1968) series of Vem-books (2005-2015; Who? series). There is a dual manifestation of a prominent feminist approach and feminist content, in form as well as in theme.

For a long time, children’s books have engaged with gender through various form devices. Writers transpose, transgress, or pass comment on traditional gender roles and devise feminist discourses. A recent example is Louise Windfeldt’s Den dag Rikke var Rasmus/Den dag Frederik var Frida (2008; The Day Rikke was Rasmus/The Day Frederik was Frida), in which two nursery-school children switch gender roles and names for the day. The rewriting of fairy tales is another strategy. Swedish Per Gustafsson’s (b. 1962) Prinsess series of books (2003-2013; The Princess Series) turns the traditional princess-role upside down and awards agency to the princess. Children’s literature abounds with energetic, rebellious, and outspoken Pippi-like girls as well as its opposite: the quiet, ordinary girls who contextualise gender liberation.

While the depiction of liberation, emancipation, and new approaches to gender roles was a strong presence throughout the Nordic countries during the 1970s, there has been an increased focus on gender in the Swedish and Finnish-Swedish contexts in recent years. The demand for strong and powerful girls is pronounced, almost predominant, and one may find a range of consciously multi-faceted portrayals of girls addressing the complexity of gender.

Narrative conventions in children’s books and adult fiction influence one another. The Finnish-Swedish writer, Monika Fagerholm (b. 1961), has spawned a number of literary descendants in YA fiction and graphic novels thanks to her compelling portrayals of girls, e.g. DIVA. En uppväxts egna alfabet med docklaboratorium (en bonusberättelse ur framtiden) (1998; Diva. Alphabet of an Adolescence with a Laboratory of Dolls (A Bonus Tale from the Future).

This new way of portraying girls is expressed through breaches of norms, forms, and conventions in addition to experiments with narrative voices and the graphic design of books. Late modernist novels in Sweden and Finland are marked by a generational change, where feminist narrative structures are explored (Söderberg & Frih 2010, Söderberg, Österlund & Formark 2013, Lövgren 2016). This development goes hand in hand with an increased scholarly focus on the figure of the girl, in Sweden and Finland in particular, as seen in the FlickForsk! Nordic Network for Girlhood Studies and the publication of the research anthology, Flicktion: perspektiv på flickan i fiktionen (2013; Perspectives on the Girl in Fiction). (Eva Söderberg & Anna Karin Frih: En bok om flickor och flickforskning. Studentlitteratur, 2010; Eva Söderberg, Mia Österlund & Bodil Formark (eds.): Flickan. Perspektiv på flickan i fiktionen, Universus Academic Press, 2013; Karin Lövgren: Att konstruera en kvinna. Berättelser om normer, flickor och tanter. Nordic Academic Press, 2016).

The gender repertoire in books has evolved and changed in line with the development of a feminist research perspective on girl and boyhood studies (Slettan 2009, Öhrn 2009). In Sweden in particular, publishers such as Olika and Sagolikt represent an expressly ideological stance focussing on diversity and a norm critique where gender is presented as a construction. Dominant stereotypes, including heteronormativity and traditional parenthood, are also questioned in everything from illustrated books to YA fiction. From picture books to YA fiction, one finds a playful approach to form by the use of ‘gurlesque’ features such as reclaiming the pink girlhood and combining character traits such as strength, danger, and rebelliousness. Gurlesque alludes to the Japanese concept of ‘kawaii’, meaning cute, a form that may also assume grotesque, macabre, and erotic undertones. (Svein Slettan: Mannlege mønster. Maskulinitet i ungdomsromanar, pop og film, Agder UP. Fakultetet for humaniora og pedagogikk, 2009; Magnus Öhrn: I pojklandet. En första kartläggning av pojkarnas territorium i svensk barn- och ungdomslitteratur”. Tidskrift för litteraturvetenskap 1, 2009.

Notable Female Creators of Picture Books in the Nordic Countries

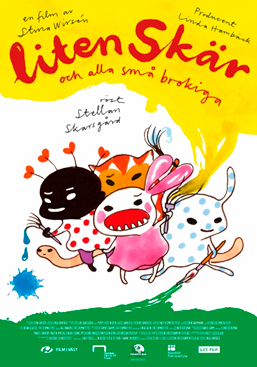

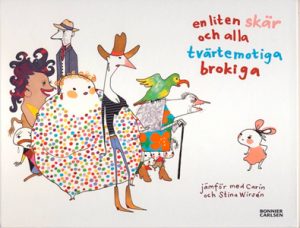

In the liten skär book series (2006-2014; Little Pink series), Swedes Carin Wirsén (b. 1943) and her daughter, Stina, mentioned above, portray the girl, Little Pink, within the parameters of an expansive gender repertoire. Little Pink goes from being a diffident, tidy girl to a gurlesque and extrovert character who wears a shocking pink frock, her fiery-red mouth opened to expose sharp fangs (Österlund 2008). The picture books address the theme of diversity through variegated characters sporting bodies of various sizes and clothed in colourful unisex outfits. Fat female bodies are depicted in a positive light as an expression of revolt against anti-fat prejudices. With Little Pink in the lead, the same group of characters feature in Wirsén’s picture books, which are characterised by keywords such as diversity and norm critique. In illustrated and picture books and animation films, Wirsén presents a poetics of diversity, e.g. by introducing a palette of intersectionality, i.e. a range of class, ethnic, and gender affiliations. A character such as the black girl, Lilla hjärtat, or Little Heart, provoked a heated debate on the depiction of ethnicity. Lucia, a wheelchair user, and characters of indefinite genders also feature in Wirsén’s repertoire. (Mia Österlund: “Se så söt du blir i den där! Maktforhandling ur genusperspektiv i Carin och Stina Wirséns bilderböcker”. Barnboken 2, 2008; “Att formge en flicka. Flickskapets transformationer hos Pija Lindenbaum ock Stina Wirsén”, Flicktion. Perspektiv på flickan I fiktionen. Universus Academic Press, 2013).

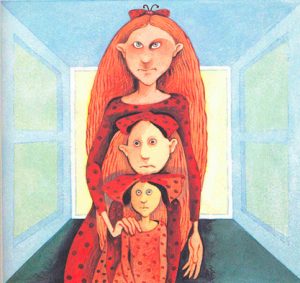

In the work of Danish writer and illustrator, Dorte Karrebæk (b. 1946), there is a general theme of sensitive yet strong girls who learn to cope on their own – even in difficult circumstances. The focus is often on the experiences and emotions – whether they be positive or negative – of the child. Pigen der var go’ til mange ting (1996; The Girl Who Was Good at Many Things), a principal work in Karrebæk’s oeuvre as writer and illustrator, depicts a girl’s development from being frail, amenable, and passive to literally breaking out from the narrow confines of a dysfunctional family. Upon the realisation of the impossibility of changing the family circumstances, she “forgot her childhood and starting growing as quickly as she possibly could.” Subsequently, she abandons her home. Childhood and girls’ lives are depicted not as biological facts but rather as a choice: if one does not have caring parents, one must learn to fend for oneself. The book sends an unequivocal message to the readers about the possibility of influencing the identity and (gender) roles they choose to assume.

In recent years, Dorte Karrebæk has made a virtue out of lending a voice to vulnerable children in collaborative efforts with the writer Ole Dalgaard (b. 1950) whose nom de plume is Oscar K. The gender perspective is most pronounced in the illustrated novel, Benni Båt (2005; Benni Boom), which questions unambiguous understandings of gender and sexuality.

The Swedish writer, Pija Lindenbaum (b. 1955) examines gender in her series of books about a girl called Gittan (2000-2011) as well as her books, Lill-Zlatan ock morbror raring (2006; Mini Mia and Her Darling Uncle, 2007), Kenta och barbisarna (2007; Ken and the Barbie Dolls), and Siv sover vilse (2009; Siv Sleeps Astray). (Åsa Warnquist: “Att vägra normen ock att omsluta den. Pija Lindenbaum som normkritiker”, Barnlitteraturens värden ock värderingar, Sara Kärrholm & Paul Tenngardt (eds.). Studentlitteratur, 2012; Mia Österlund: ”Queerfeministisk bilderboksanalys. Exemplet Lindendaum”. Queera läsningar. Rosenlarv, 2012; ”Att formge en flicka. Flickskabets transformationer hos Pija Lindenbaum och Stina Wirsén”, Flicktion. Perspektiv på flickan i fiktionen. Universus Academic Press, 2013).

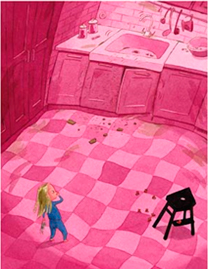

The Gittan series makes its mark by portraying a reticent girl who relies on her own forms of problem-solving by resorting to emancipatory fantasies referencing traditional fairy tale motifs such as Little Red Ridinghood and the wolf. Lindenbaum typically introduces multitudinous depictions of everyday life, thereby presenting alternative ways of life and nuanced perceptions of gender to the reader in an understated and elegant manner. In Siv sover vilse, a book viewing friendships from a class perspective, the name of the girl, Cerisia, is a rose-coloured word play, and her entire home is transformed through a shocking pink filter in the eyes of her guest, the girl Siv. In this kind of mindscape set between dream and reality, Siv’s thoughts and emotions are coloured by the visual narrative form.

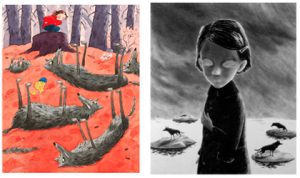

The extensive oeuvre of the Norwegian writer, Gro Dahle (b. 1962), demonstrates how seemingly fragile girls may gain strength and a voice of their own. A remarkable transformation of a girl occurs in the story, Snill (2002; Nice). The reader is introduced to Lussi, who is unbelievably prim and proper and capably adapts to the parameters and norms of any given order: “Because Lussi does everything she is supposed to. /Look how she smiles! / Writes neatly, reads from books, and nods and smiles, and raises her hands.” Svein Nyhus’ illustrations depict the delicate little girl dressed in pink with a white collar, bows in her neat hair. However, given that she disappears, literally fading into the wallpaper, she is hardly presented as an ideal, (Ommundsen 2004). The illustrations continue with what is probably the most formidable outburst of rage in the history of Nordic picture books. (Åse Marie Ommundsen: “Kanskje det fins flere osynlige jenter? Bildeboka Snill av Gro Dahle og Svein Nyhus”. Barneboklesninger. Norsk samtidslitteratur for barn og unge. Fagbokforlaget, 2004).

To the text, “Enough!”, we see an image of a child, whose violent anger scares the adults at first, and who, by the end of the story, appears more grubby, with messy hair, but also looks the reader straight in the eye with a wry smile and a finger in her nose – a clear indication of the acceptance of the child, who rebels against restrictive norms and systems. In the works of Wirsén, Karrebæk, Lindenbaum, and Gro Dahle/Svein Nyhus, contemporary tales of a girl’s development verge on being an invitation to breach rigid and inconvenient boundaries.

Graphic Novels: Breaches of Form and Norm in Aberrant Stories

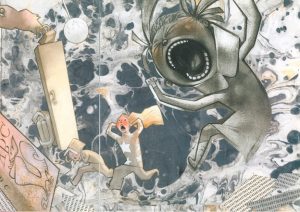

Female creators of comic strips work within a tradition of raising awareness and encouraging protest. (Jönsson 2014; Österlund 2014). They incorporate gurlesque elements where bold femininity combines with traditional ‘girlish’ features while depictions of decline, illness, and uneasiness is directly associated with girls’ bodies and girlhood norms. The Swedish writer, Anna Höglund’s (b. 1958) YA graphic novel, Att vara jag (2014; To Be Me) uses the signal colour, cherry pink, which social anthropologist, Fanny Ambjörnsson, has argued represents a sort of militant pink protest, a playful gurlesque approach, as well as processes of normalisation. (Maria Jönsson: “Ironiska, groteska och reparativa strategier i samtida feministisk seriekonst”. Finsk tidsskrift 3-4, 2014; Mia Österlund: ”Gränsöverskridande grafiska romaner. En hemtam hybridform för unga läsare”. Mötesplatser. Texter för svenskämnet. Studentlitteratur, 2014).

Höglund’s book opens with the image of a girl studying her genitals in a mirror – a reference to the call during previous decades for practices that would reinforce girls’ and women’s body awareness. A meta perspective runs through the book: Höglund dissects historical events from a feminist perspective in the spirit of the Swedish feminist comic-strip creator, Liv Strömqvist. During the 1990s, Höglund experimented with feminist picture books about Syborg, read: cyborg, cf. the American gender scholar Donna Haraway’s term for a creature that is half human and half machine, in Resor jag (aldrig) gjort av Syborg Stenstump, nedtecknade av Anna Höglund (1992; Journeys I (Never) Embarked Upon by Syborg Stonepiece, Recorded by Anna Höglund) (Söderberg 2009). Höglund’s alternation between genres and target groups points to the work of older female writers and artists such as Swedish Inger Edelfeldt, who writes adult and YA novels in addition to illustrating the series about Hondjuret, or the She-Animal. (Eva Söderberg: “Upptäcktsläsning i Resor jag (aldrig) gjort, av Syborg Stenstump. Nedtecknade av Anna Höglund”. Barnboken 32, 2009).

The aesthetics in Lani Yamamoto’s Icelandic picture book, Stína Stórasæng (2013; Stina Big Duvet), is somewhere on the boundary between picture book and graphic novel and established a link to knitting as a form of traditional women’s culture. The tactile design of the book takes its inspiration from knitting and there is a special edition available sporting a knitted woollen cover and mittens attached. The theme of coldness and being cold is related to the creativity of the girl, Stina, and the character trait of idleness is associated with her ingenuity.

One finds a similar focus on the exploration of girlhood in the new age category of ‘tweens’ in Psst! (2013) by Annette Herzog (b. 1960) and Katrine Clante (b. 1973), a hybrid between picture book and graphic novel. Here, too, there is a focus on the artistically creative girl. The visual aspect of the book presents her as seen from the outside in addition to a staging of the girl’s own drawings, collages, and handwriting, addressing thoughts about family and identity, as well as incipient bodily changes and gender identity.

The feminist graphic novel characteristically occupies a boundary space, where stories of adolescence and normbreaking are problematised by way of a gender perspective. Norwegian Inga Sætre’s (b. 1978) graphic crossover novel, Fallteknikk (2011; Falling Technique) is executed in a genre-typical, ugly-beautiful, and humorous style and relates the story of a teenage pregnancy. Sætre also created the series, Møkkajentene (Grubby Girls), published in the Morgonbladet newspaper, which portrayed the daily life and reflections on gender of a vulnerable but quick-witted girl duo. Sætre belongs to the tendency among feminist comic-strip creators who portray ordinary girls ‘with an attitude’. It takes the form of a poetic picture journal containing reflections about, for example, standing out and not fitting in.

Rebellion and Experiment in Fantasy and Dystopia

Fantasy stories and dystopias provide the opportunity to stage extreme settings and radical visions of gender utopia or dystopia. At best, the sense of doom is followed by liberation from static gender repertoires. In Swedish authors, Sara Bergmark Elfgren (b. 1976) and Mats Strandberg’s (b. 1976), Engelsfors Trilogy – Cirkeln (2011; The Circle, 2012), Eld (2012; Fire, 2013), and Nyckeln (2013; The Key, 2015) – six fundamentally different girls get together in a desolate public park. As witches, they must save the world and to that end they are obliged to collaborate. Elements of Nordic noir and fantasy are combined with the YA novel’s accounts of friendships and love, budding sexuality, drugs, and endeavours to find one’s own course in life. Focussing on girls’ power, the trilogy has been adapted into film and graphic novel, too.

Jessica Schiefauer’s (b. 1978) Swedish novel, Pojkarna (2013; The Boys) combines fantasy and magic realism (Fokin 2015). A trio of vulnerable girls are transformed into boys by ingesting the juice of a plant. With a multiplied gender repertoire, the girls explore their possibilities, bodies, and the boundaries of friendship. The narrative form is suggestive and the style lyrical, while the themes are both brutal and sensual. (Rebecka Fokin: “’En människa är det’. Flickskap i Jessica Schiefauers Pojkarna”. Barnboken 38, 2015).

The legacy from the Nordic sagas and folklore is also reworked into fantasy stories. Finnish-Swedish Maria Turtchaninoff’s (b. 1977) Underfors (2010; Underville) is set in a town beneath Helsinki where gender and generational issues are played out through the folkloric figure of the troll. Finnish-Swedish Annika Luther’s (b. 1958) topical YA novels are marked by environmental disasters and questions of immigration and ethnicity. In the eco-dystopia, De hemlösas stad (2011; City of the Homeless), the environmental cataclysm has occurred, migratory surges battle for control of land while the protagonist searches for her roots in this dystopian landscape.

A number of works by female, Nordic writers working within the Nordic noir tradition are characterised by dark, snow-covered landscapes and depictions of the welfare state’s more violent side. Finnish Seita Vuorela’s (1971-2015) Karikko (2012; The Reef) is set in a dark and desolate campsite. There is a series of boy characters and a central girl figure in the mythical account of sudden young death, which features elements from sagas and myths. Finnish Salla Simukka’s (b. 1981) trilogy about Lumikki (Snow White) Andersson, Valkoinen kuin lumi (2013; As White as Snow, 2015), Punainen kuin veri (2013; As Red as Blood, 2014), and Musta kuin eebenpuu (2014; As Black as Ebony, 2015), has achieved international recognition. The novels about Lumikki reference suspense novels, while the girl’s life is framed by identity conflicts and a romantic relationship with a transgender person.

The Northern Norwegian Sami fantasy novel, Ilmmiid gaskkas/Mellom verdener (2013; Between Worlds) by Máret Ánne Sara (b. 1983) portrays two Sami siblings preoccupied with shopping and motor sports, who vanish into thin air. The novel crosscuts between everyday life and underground sequences, interweaving Sami folklore with the contemporary perspective of the YA novel.

The fantasy genre – and its concomitant, often notable, female protagonists – operates across media as seen in Lene Kaaberbøl’s (b. 1960) fantasy tetralogy, The Shamer Chronicles, initiated with Skammerens datter (2011; The Shamer’s Daughter, 2004). Today, child readers may meet the extraordinary girl character, Dina, in books, on film, and as a character in a musical. Kaaberbøl’s portraits of girls and women who fight on an equal footing with men creates, through the magical powers of Dina, a link with the potent and dangerous female characters harnessing supernatural capabilities of earlier times, while concurrently demonstrating how even very popular publications are implicated in the rewriting of traditional gender roles (Bissenbakker 2014). Other popular and eloquent fantasy writers, such as Cecilie Eken (b. 1970) and Josefine Ottesen (b. 1956), combine a well turned plot with strong and nuanced portraits of girl characters, too.

YA Novels as Gender Laboratory

After the turn of the millennium, we see examples of a kind of ‘dual liberation’ in the works of female writers: a liberation from norms about girls’ identities as well as general norms concerning youth. Every single dimension of girlhood is examined in detail, creating more complex and nuanced accounts expressed through changing narrative perspectives and motifs.

Norwegian Hilde Hagerup’s (b. 1976) portrayals of girls in Høyest elsket (2000; Dearly Loved) and Løvetannsang (2002; Dandelion Song) are concerned with girls affected by traumatic childhood experiences. Form and style are characterised by polyphony and gothic motifs such as mysterious houses and landscapes. A complex girl character is shaped through the linguistic exploration of the meanings of being a girl (Bjørkøy 2015). In a range of novels, the writers provoke a sense of doubt or hesitation in the reader by letting several events be narrated by multiple voices, or by creating doubts about the nature of narrative categories suspended between dream and reality. Faroese writer, Marjun Syderbø Kjelnæs’ (b. 1974) Skriva i sandin (2010; Write in the Sand) is an example of this. The novel is about ten youths in Thorshavn, whose paths cross, and where each character offers the reader a new perspective on the events of the novel. Five of the characters are female and gender plays a pivotal role in the novel, which covers the usual motifs of YA novels, such as friendship, sexuality, and the search for identity (Aasta Marie Bjorvand Bjørkøy: “Når fuglen flyr: Høyest elsket som eksperimentell utviklingsroman”. Barnboken 38, 2015).

Female writers depict relationships between girls on a continuum from friendship to lesbian relationships. The stories are peppered with humorous and grotesque elements, e.g. Swedish Sanne Näsling’s (b. 1983) Kapitulera omedelbart eller dö (2011; Capitulate Immediately or Die), which, in the tradition of gurlesque, weaves together a number of different perceptions about how girls can and ought to be. The girl’s bedroom is the central locus for the preparation and testing of different approaches. Several novels contain manifestos for girlhood where girls take a stand on the expectations they come up against. Sanne Näsling refers to a number of feminist texts by Simone de Beauvoir, Valerie Solanas, and Monika Fagerholm. Näsling uses an experimental form, where the boundaries between layout and text is blurred, leaving the reader unsure of whether the story is imagination or reality, e.g. when the girls simultaneously create a picture of their dreams for the future and fictional artists’ identities bearing animal characteristics.

Experiments with form and animal metamorphoses take centre stage in Swedish Aase Berg’s (b. 1976) verse novel, Människoätande människor i Märsta (2009; People-Eating People in Märsta), as three teenage girls are transformed into animals and ridicule current social and gender norms. Berg, like Näsling, aligns herself with a tradition of female artistic practices, e.g. the poem, Gorilla Girl, where one of the girls – inspired by the feminist group of artists, Guerilla Girls, who staged a protest in 1985 against the minor representation of women at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City – photographs herself wearing a gorilla mask.

In valoa valoa valoa (2011; light light light), the Finnish writer, Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen (b. 1977), plays with form by calling on the reader to tear up the first pages of the book – if they find them wanting – and she frequently passes meta-level commentary on the act of writing. The multi-layered lesbian tale, which unfolds under the shadows of the Chernobyl disaster, concerns itself in various ways with contraventions of social norms, e.g. Huotarinen’s retrospective first-person narrator, who juxtaposes the girl’s masturbation and her critique of society, yet concludes with a warm, sensual and humorous description of the girl’s erotic play with the globe:

“The plastic was slippery in my sweaty hands. I felt the globe glow like burning coal, sending those red and blue and yellow messages pulsing through my body from every country and city and ocean and beach.

Dearest readers! You too, have childhood experiences of masturbation. It is nothing special. However, I do find it important to note that I was holding on to a globe.”

What is called ‘flickmaktflickor’, or girlpower girls, in a Swedish context, i.e. girls who rebel against restrictive gender roles for girls, have dominated Swedish literature in particular, and new counter images have emerged. In Anna Charlotta Gunnarsson’s (b. 1969) novel, Utan titel (2012; No Title), the ordinary girl chooses to protest by not standing out: “[…] my sparse mascara, my on-trend, yellow H&M clothes, and pale pink lips, my indifferent attitude […] Who would have thought that you would turned out so… ordinary. Daddy pronounces ‘ordinary’ in a drawn-out manner, as if it were odd”.

A Multiplicity of Upheaval: Ethnicity, Gender Issues, and Sexuality

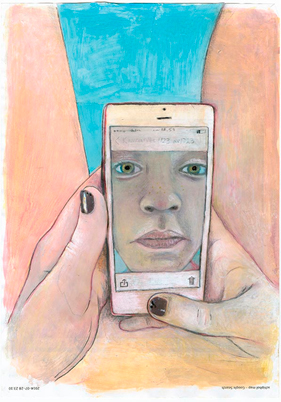

Today, the boundary between children’s literature and adult fiction is becoming increasingly fluid. The Greenlandic writer, Niviaq Korneliussen’s (b. 1990), novel, HOMO sapienne (2014; HOMO sapienne), may be taken as a concluding example of a literature in which established gender roles, ethnic and national concepts of identity, and the demarcation of target groups come into play. The novel follows a group of youths trying to find their way in a world limited by heterosexual norms and traditional gender roles. The young Greenlanders’ awareness of bi- and homosexuality and transgenderism unfolds in the mediated contemporary world of Facebook, mobile telephones, and e-mails, while a meta-postcolonial impression of Greenland is concurrently depicted, e.g. the response of one of the protagonists after attempting to extrapolate the source of their adversity: “Enough of that post-colonial piece of shit”.

The typical protagonist of Nordic children’s literature continues to be white and middle class. Norwegian Iram Haq’s (b. 1976) picture book, Skylappjenta (2009; Little Miss Eyeflap), and Danes, Özlem Cekic (b. 1976) and Christina Aamand (b. 1972), in whose works girls from ethnic minority backgrounds struggle in order to find a position between the given order in their families and the norms and prejudices of the surrounding society, are exceptions to the rule.

There are striking and thought-provoking national differences when considering contemporary children’s and YA literature from a gender perspective. It is clear that issues pertaining to gender, body, sexuality, identity, and power play a considerable role and that a Nordic readership has every possibility to encounter alternatives to gender stereotypes. Children’s literature articulates and stages childhood and youth as a period of time, which is diverse and offers individuals the ability to influence their own identities while being concurrently characterised by unpredictable, mutable, and severe living conditions.

Fiction

- Aase Berg: Männiksoätande människor i Märsta. Natur och Kultur, 2009

- Gro Dahle og Svein Nyhus (illust.): Snill. Cappelen, 2002

- Sara Bergmark Elfgren og Mats Strandberg: Cirkeln. Rabén & Sjögren, 2011. The Circle, Random House, 2012

- Sara Bergmark Elfgren og Mats Strandberg: Eld. Rabén & Sjögren, 2012. Fire, Random House, 2012

- Sara Bergmark Elfgren og Mats Strandberg: Nyckeln. Rabén & Sjögren, 2013. The Key, Random House, 2013

- Monika Fagerholm: DIVA. En uppväxts egna alfabet med docklaboratorium (en bonusberättelse ur framtiden). Söderströms, 1998.

- Anna Charlotta Gunnarsson: Utan titel. Rabén & Sjögren, 2012

- Hilde Hagerup: Høyest elsket. Aschehoug, 2000.

- Hilde Hagerup: Løvetannsang. Aschehoug, 2002.

- Iram Haq: Skylappjenta. Cappelen Damm, 2009

- Annette Herzog og Katrine Clante (illust.): Pssst! Høst, 2013

- Vilja Tuulia Huotarinen: valoa valoa valoa. Karisto, 2011.

- Anna Höglund: Resor jag (aldrig) gjort av Syborg Stenstump, nedtecknade av Anna Höglund. Bonnier, 1992

- Anna Höglund: Att vara jag. Lilla Piratförlaget, 2014

- Oscar K. og Dorte Karrebæk (illust.): Benni Båt. Dansklærerforeningen, 2005

- Dorte Karrebæk: Pigen der var go’ til mange ting. Forum, 1996

- Marjun Syderbø Kjelnæs: Skriva i sandin. Bókadeild Føroya Lærarafelags, 2010.

- Pija Lindenbaum: Else-Marie och småpapporna. Rabén & Sjögren, 1990. Else-Marie and Her Seven Little Daddies, Henry Holt & Co, 1991

- Pija Lindenbaum: Lill-Zlatan och morbror raring. Rabén & Sjögren, 2006. Mini Mia and Her Darling Uncle, R & S Books, 2007

- Pija Lindenbaum: Kenta och barbisarna. Rabén & Sjögren, 2007.

- Pija Lindenbaum: Siv sover vilse. Rabén & Sjögren, 2009.

- Annika Luther: De hemlösas stad. Söderströms, 2011

- Sanne Näsling: Kapitulera omedelbart eller dö. Rabén & Sjögren, 2011

- Jessica Schiefauer: Pojkarna. BonnierCarlsen, 2013.

- Salla Simukka: Punainen kuin veri. Tammi, 2013. As Red as Blood, Skyscape, 2014

- Salla Simukka: Valkoinen kuin lumi. Tammi, 2013. As White as Snow, Skyscape, 2015

- Salla Simukka: Musta kuin eebenpuu. Tammi, 2014. As Black as Ebony, Skyscape, 2015

- Inga Sætre: Fallteknikk. CappelenDamm, 2011

- Maria Turtschaninoff: Underfors. Söderströms, 2010

- Seita Vuorela: Karikko. WSOY, 2012.

- Louise Windfeldt og Katrine Clante (illust.): Den dag Rikke var Rasmus/Den dag Frederik var Frida. Ministeriet for ligestilling, 2008

- Lani Yamamoto: Stína Stórasæng. Crymogea, 2013.

Non-Fiction

- Mons Bissenbakker: ”How to bring your daughter up to be a feminist killjoy: Shame, accountability and the necessity of paranoid reading in Lene Kaaberbøl’s The Shamer Chronicles”. European Journal of Women’s Studies 21, 2014

- Aasta Marie Bjorvand Bjørkøy: ”Når fuglen flyr: Høyest elsket som eksperimentell utviklingsroman”. Barnboken 38, 2015

- Nina Christensen: ”I bevægelse. Billedbøger og billedbogsforskning under forvandling”. Tidsskrift för litteraturvetenskap 2, 2014

- Nina Christensen: ”At blive den, man er. Om Dorte Karrebæks barndomserindring i tilfælde af krig”. Till en evakuerad igelkott, Maria Lassén-Seger og Mia Österlund (red.). Makadam Forläg, 2012

- Marah Gubar: ”Risky Business: Talking about Children in Children’s Literature Criticism”. Children’s Literature Associtation Quarterly 38, 2013

- Rebecka Fokin: ”’En människa är det’. Flickskap i Jessica Schiefauers Pojkarna”. Barnboken 38, 2015

- Maria Jönsson: ”Ironiska, groteska och reparative strategier i samtida feministisk seriekonst”. Finsk tidsskrift 3-4, 2014

- Karin Lövgren: Att konstruera en kvinna. Berättelser om normer, flickor och tanter. Nordic Academic press, 2016

- Åse Marie Ommundsen: ”Kanskje det fins flere osynlige jenter? Bildeboka Snill av Gro Dahle og Svein Nyhus”. Barneboklesninger. Norsk samtidslitteratur for barn og unge, Svein Slettan og Agnes-Margrethe Bjorvand (red.). Fagbokforlaget, 2004

- Svein Slettan: Mannlege mønster. Maskulinitet i ungdomsromanar, pop, og film, Agder UP, Agder. Fakultetet for umaniora og pedagogikk, 2009

- Eva Söderberg: ”Upptäcktsläsning i Resor jag (aldrig) gjort, av Syborg Stenstump. Nedtecknade av Anna Höglund”. Barnboken 32, 2009

- Eva Söderberg, Mia Österlund og Bodil Formark: Flicktion: perspektiv på flickan i fiktionen. Universus Academic Press, 2013

- Eva Söderberg og Anna-Karin Frih: En bok om flickor och flickforskning. Studentlitteratur, Lund 2010

- Åsa Warnquist: ”Att vägra normen och att omsluta den. Pija Lindenbaum som normkritiker”. Barnlitteraturens värden och värderingar, Sara Kärrholm og Paul Tenngardt (red.). Studentlitteratur, 2012

- Ebba Witt-Brattström: ”Nummulitens hämnd. Tove Jansson”. Ur könets mörker. Litteraturanalyser av Ebba Witt-Brattström. Norstedts, 1993

- Magnus Öhrn: ”I pojklandet. En första kartläggning av pojkarnas territorium i svensk barn- och ungdomslitteratur”. Tidskrift för litteraturvetenskap 1, 2009

- Mia Österlund: ”Se så söt du blir i den där! Maktförhandling ur genusperspektiv i Carin och Stina Wirséns bilderböcker”. Barnboken 2, 2008

- Mia Österlund: ”Queerfeministisk bilderboksanalys. Exemplet Lindenbaum”. Queera läsningar, Katri Kivilaakso, Ann-Sofie Lönngren & Rita Paqvalen (red.). Rosenlarv, 2012

- Mia Österlund: ”Att formge en flicka. Flickskapets transformationer hos Pija Lindenbaum och Stina Wirsén”, Flicktion. Perspektiv på flickan i fiktionen, Eva Söderberg, Mia Österlund & Bodil Formark (red.). Universus Academic Press, 2013

- Mia Österlund: ”Starka flickor i nordisk bilderbok. Hur bilderboksflickan gestaltas av Pija Lindenbaum och Stina Wirsén”. Jenter og makt! Kari Skjønsberg-dagene 2013 Bibliotheca Nova 2, 2013

- Mia Österlund: ”Gränsöverskridande grafiska romaner. En hemtam hybridform för unga läsare”. Mötesplatser. Texter för svenskämnet, Ann Boglind, Per Holmberg og Anna Nordenstam (red.). Studentlitteratur, 2014