The Danish clergyman’s wife Eline Boisen (1813-1871) wrote because she could not not write. She wrote memoirs, and she wrote from huge bitterness and anger, wrote herself out of her isolation and loneliness: “I am trapped between four walls,” she writes symbolically in her preface; writing was the creative force that connected her with the world.

When she died, in 1871, she left forty-seven closely-written exercise books, more than one thousand pages; in a testamentary letter she entrusted the books to her son, Frede Bojsen, a well-known Venstre (Liberal Party) politician. He saw to it that his mother’s handwritten autobiography was transcribed by typewriter, and he deposited a copy at Rigsarkivet (the Danish State Archives) in order to safeguard her life’s work for posterity. At the same time, however, Eline Boisen was somewhat muzzled because a clause was attached stating that no information concerning her marriage was to come into the public domain given that the memoirs gave an “in essence, misleading impression of our parents’ relationship”.

The forty-seven exercise books were stored away, but they came to light again in 1986; it turned out that Frede Boisen had not deposited a complete transcription. The exercise books are full of crossing-out, especially when the text deals with the most painful periods in Eline Boisen’s marriage.

Most memoirists start writing about their lives in their old age, and looking back on the course of their life, they often see it at a distance and in a clarifying light. Eline Boisen, on the other hand, was midway through her life when she began writing; she focused on the most painful aspects and wrote almost up until the day she died.

Her memoirs, like Sophie Thalbitzer’s Grandmamas Bekiendelser (1807; Grandmama’s Confessions), can be read as an account of a ‘fall’, the loss of original innocence and happiness, in which a Norwegian childhood, as the apple of her father’s eye, is depicted in paradisiacal terms: “I see it before my eyes in a magic radiance, and more so as my later life grew increasingly bitter and onerous.” In her autobiography, childhood is the only period to be depicted as an idyll, and Eline Boisen evokes an ideal image of autocratic society. Her father was a highly-placed official in the silver-mining town of Kongsberg, and he took care of the lowest stratum, the impoverished mine workers, like a father takes care of his children. The class society under an absolute monarchy is depicted as a harmonious and orderly whole, in which everyone knows their place and feels secure there. Sitting atop the pyramid is the good king, father of the country, and he looks after his subjects.

Eline Boisen’s lifelong yearning for ‘father’s house’ was written against a backdrop of loss: at the age of nine she suddenly lost everything – her father, her country, and her social status, and she never got over this ‘fall’. She spent the years that followed living with her mother and her younger siblings in a small flat in Copenhagen. Her mother never came to terms with these major changes; she became ill with cancer and deepening paranoia. Eline had to be mother both to her mother and to her young siblings. But nothing she did was ever good enough. She therefore developed a highly self-critical attitude, and for the rest of her life she suffered from a fundamental sense of guilt. This also colours her depiction of the world around her: most of those who cross her path are skewered with a few strokes of her pen, and in the role of narrator she has a slightly oblique, almost x-ray gaze.

Writing about Søren Kierkegaard, Eline Boisen reports: “Once, before I had moved from the city, I saw him court with great persistence a little girl who had not yet been confirmed; – she later became his fiancée. She, with whom he played so disgraceful a game for so many years, and from whom he eventually departed, without breaking off the relationship – and without saying where he was going.”

It is as if she is standing out in the wings, meticulously recording what is going on. Her intensely personal text thus has an occasionally modern, impressionistic air.

Eline Boisen lived at a time when the autocratic society was in the process of dissolution. From 1837 until 1850 she was the clergyman’s wife in the little village of Skørpinge in the west of Jutland, and here she lived in the midst of a religiously and politically mutinous rural movement. She describes it as a frenetic and angry movement with revelations and visions. The poor people felt that their time had now come; the heavens themselves had opened and proclaimed that those at the top of the social pyramid must give way to the people. The upshot was that the people were rising in rebellion against the authorities; Eline Boisen remained, however, a believer in absolute monarchy all her days.

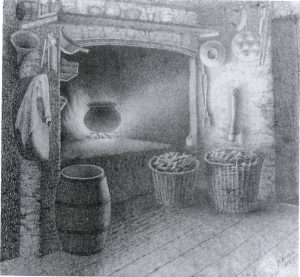

As a clergyman’s wife in the countryside, she was mistress of a large, self-sufficient household, and was dependent on the servants knowing their place and being obedient. And then she, for her part, would take care of them. If the feudal practice of reciprocity between ‘master’ and ‘vassal’ did not work, then the whole system would collapse, thought Eline, and that was exactly what happened in Skørpinge, where the servants were devout and did only what suited them. Eline Boisen saw this as a striking illustration of how democracy was systematised egoism and a free-for-all. She eventually started employing one “Child of the Earth” for each “Child of God”, as the revivalist community called themselves, so that work in the pastor’s household did not go unattended.

“This winter we navigated incredibly choppy waters. – That Sophie was basically wild. – I put up with everything – without the least grumble. – Sophie did no more than she chose; – So Mie the nursemaid brought little Karen to me – when Sophie ran off – and then Sophie came and told me about all manner of revelations: – She dare not milk the cows – for the Devil would be after her – and then she scared little Sine Jensen, so they charged through the rooms with a dog in pursuit. – I could see neither dog nor Devil, but they could see both. – Sophie dashed in and out of the windows, and as far as I could tell she was raving mad.”

She wrote in order to find an identity in a strange, alien world in which, it seemed to her, demonic forces had been let loose. There is no overarching structure to the memoirs apart from the purely chronological. The act of writing was of a clearly therapeutic nature, and once she had started, the words flowed from her pen. She has a disconnected style with countless dashes, and the narrative switches between dramatic, theatrical accounts, straightforward reporting, and general reflection. At the same time, she makes a higgledy-piggledy mixture of significant and insignificant, highlight and everyday occurrence, and the main story – her own life story – is interwoven with any number of secondary stories.

Were Boisen’s Heart to be Mine…

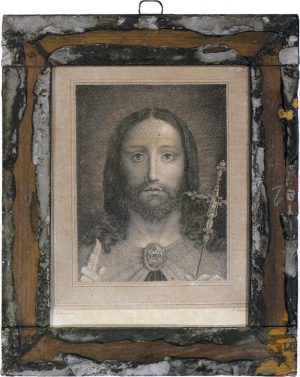

Love as fate – marriage with the clergyman F. E. Boisen – is the thread that holds the fragmentary memoirs together, and the theme is followed by means of an elementary dramatic structure around her lifelong wish for “Boisen’s heart to be mine”. She writes with raw honesty about her ambivalent relationship to her husband: she loved him all their life together and longed for his love, while also despising him for letting her down. Boisen is portrayed as an intensely passionate and emotional man. He has huge mood swings, whereas she comes across as rational, matter-of-fact, and reserved. “I who was always so sparing with caresses in general, and particularly with kisses,” as she writes plaintively when one of the poor-house women in Skørpinge “not only took me by the hand with her scabby fist, but on top of that she gave me a kiss, a real smack, in thanks, as a sister, because I accepted her handshake”. Ever since she lost her father when she was nine years old, she had an intense yearning for love, and she carried a romantic dream of the grand, redemptive love. She saw marriage as a symbiotic relationship with “one soul in two bodies”; the reality, however, was that of two totally different characters on either side of a huge divide, and in perpetual conflict. Eline only experienced Boisen’s love in flashes – on the occasions when he was about to lose her – and her longing gradually turned its attention towards heaven: “Jesus, Jesus is the object of all the longing in my heart.” Here she lays bare all her emotions in an erotically-tinged, pietistic language: “[…] sweet Jesus, most blessed Saviour, take me in Your arms.”

This World is not for Women and Children

Eline Boisen came from a cultured, bourgeois background, and as a clergyman’s wife she was on the upper rungs of the social ladder. But for most of her life she wore rural attire, and she shared the lot of the peasant women, most conspicuously in the village of Skørpinge. She describes life here in a large, damp house with just one stove; there was a draught from the cellar, and clods dropped from the ceiling onto the heads of people below. The floorboards were rotting, there was moisture on the inside walls, which froze to ice in winter, and the children got frost-bitten hands at night.

For twenty years, Eline Boisen was almost continuously pregnant; between 1835 and 1854 she gave birth to eleven children, of which three died as toddlers. Her memoirs provide an insight into an incredibly harsh female existence; illness and death were daily companions, and curative procedures were ancient: blood-letting, application of leeches, and various poultices, mustard or Spanish fly to draw fluid and matter from the body. Every birth was an open question as to whether she and the child would survive, and all of her eleven children nearly died within their first year.

She already felt old and worn-out by the time she was forty-three, and she expected to die before long. In 1846 Eline is sitting by her two-year-old Otto’s deathbed. His condition is gradually deteriorating, and when the suffering is at its height she writes: “Was it solace or surprise, that horrific night, when I could feel that I was mother to yet another soul that had claims on me? – I do not know – but all I do know is – that it called for tremendous strength to stop myself from despairing.”

It is typical of Eline Boisen’s writing style that she goes into detail when reporting painful suffering: skin ripped from the stomach of the woman in labour; the throat that closes so that the ailing person dies of starvation. She herself had an abscess in her breast for more than a year, and when describing how she got rid of it she does not miss out a single detail.

“After many days of hard and loathsome effort, she reached the nasty spot and sucked out all the badness that had been in there for more than a year. – It was truly painful for me, so I had to bite on a towel in order to lie still, but she, the calm, blessed Karen, who even swallowed this loathsomeness out of pity for me in order to relieve my suffering – she was my friend until her death.”

From the age of fourteen she suffered fits of hysteria. The fits were initially a reaction to her mother’s morbid suspiciousness and critical attitude. A growing sense of guilt found expression in physical illness. The fits gathered pace as her marriage went from bad to worse, and she suffered from the strangest illnesses which she describes as nervous ailments in origin. The hysterical symptoms seem to have stopped when, aged forty-three, she started to write. She now had an outlet for the enormous inner pressure that she had for so long vented through convulsions.

She exposes a situation for women that could just as well be from the Middle Ages; and she sees life as a battle between heaven and hell, understood just as tangibly as the medieval wall paintings with their dramatic illustrations of heaven as a castle and hell as a monstrous mouth. Her world was one full of catastrophe, lived out on the borderlines of life, and she made no sharp distinction between the visible and the supernatural. Particularly fateful happenings could often be foreseen in dreams and visions or through signs in nature, she thought; an apple tree suddenly blossoming in October, for example, was an omen of death.

Frozen landscapes and a burning inner soul are common metaphors used by nineteenth-century female writers when they want to articulate pent-up emotions and unfulfilled longings, and in this, Eline Boisen is no exception. Her illusory illnesses and illusions of death are condensed manifestations of her pent-up passions. After Otto’s death she writes: “My little boy had gone home, where he no longer needed to look through a murky pane, but directly at our Lord face to face – and up there was surely also room for his mother who, too, was a child of God – albeit in the foreign country, where there was so much snow and ice to get through.”

Eline Boisen’s Christian faith was composed of many levels. Her illness-induced delirium had traits of the medieval world picture: she had visions of Purgatory and of burning lakes with the heads of the damned visible above the surface.

“Behind us there was a burning lake, from which some screaming heads occasionally rose and cried out for help and pity, and to my horror I saw there a lot of familiar faces – yes – some who were close to me – and then I became so overcome by dread that I too slipped down close to the lake, until I heard voices saying not to look back, but only always forward, until our Lord came and helped.”

At the same time, she felt strongly attracted by an orthodox Lutheranism, in which emphasis was placed on sin and the admission of sin as prerequisites for God’s mercy. She considered suffering and death to be trials: God’s punishment meted out to the sinful person. Finally, being a child of her times, she was interested in Kierkegaard’s existentialism with its powerful accentuation of individual responsibility. In her memoirs she writes, addressing Søren Kierkegaard directly:

“Your reflections on this ‘being alone with our Lord’ – and letting Him judge one into the marrow – have been of great blessing and comfort for me, and have helped me not to make mere flesh my strength – but to fetch the oil of life from the source itself.”

In this passage, she is almost ahead of her time; but as a whole her autobiography shows that there must have been a colossal asynchronism between men’s and women’s worlds in the mid 1800s. Boisen fought, as a child of his times, for liberty and equality, whereas Eline’s world was more medieval, with catastrophe, torment, and cruel death daily realities, and she felt fundamentally alienated from her day and age.

Had I been a Truly Gentle and Pious Woman[…]

Eline Boisen describes a fundamental feeling of alienation and loneliness in the midst of the throng. She did, however, sporadically experience a sense of community with women who helped her when she was in need, or women she was able to help. Community cutting across class differences, arising from awareness of shared circumstances in which loyalty, self-sacrifice, and endurance are necessary qualities. Here, in the company of gentle, pious women, whom she would so like to resemble, she found an answer to her questions about the innermost meaning of existence; an answer that dissolved the contrasts in her image of God.

Throughout all the years in which Eline Boisen wrote her memoirs, she looked at this ideal of womanhood with the same longing as when she described her childhood before the ‘fall’. Her autobiography can be read as a revised version of the biblical myth of paradise – the Fall – and restitution through Christ and His representatives: the pious women who came to the rescue of the beleaguered souls.

“Had I been a truly gentle and pious woman, I could perhaps have helped them in both one way and another – but I needed all my strength not to be consumed in bitterness and anger – and, furthermore, my words were of so little consequence!”

Her friend Agnes Helweg came to her assistance in 1856 when her lifelong fear of perdition had again flared up. The actual cause this time was that in the 1850s, the Grundtvigians had turned Grundtvig’s “matchless discovery” of 1825 – that the Apostolic Creed was the foundation of Christianity – into a kind of magic formula. If you were not baptised according to the very letter of its wording, you could not be sure of salvation, they said.

From his philological vantage point, Grundtvig could not dismiss claims made by the historical-critical method of scholarship that the Bible was not God’s word from one end to the other. He therefore endeavoured to find out what, then, comprised the core of Christianity, and he made the “matchless discovery” that true Christianity is a living community with fellowship in the sacraments, baptism, and communion, when faith – the creed – is confessed.

Eline was profoundly affected by this and no one – not even Boisen – would help her:

“Then Helweg’s lovely Agnes came to visit me, and she delved deeply and asked if it were not the case that I had a heartfelt grief – and then it came out. She then piously said to me: ‘Yet just do not worry about what all the men in the world might say – after all, they could not change God’s heart, and His heart will carry us all home,. Just let the men engage in combat – they must have something to do – we women will trust in that God will arrange everything – if we do not love ourselves above all else, then we can believe in the goodness of God.”

In the light of the depiction of a pious and selfless Agnes, it is remarkable that her words of comfort are so combative and pithy. She must have felt that she was in possession of a truth: the core of God’s being is love, not anger, and women are privy to this insight, whereas men quarrel about unimportant, theological quibbles. Outwardly, Agnes kept her knowledge to herself, but Eline Boisen’s memoirs suggest that beyond the official Church there was an intense convention of piety among women.

Death Narratives

The memoirs as a whole undergo a clear shift from life instinct to death drive, from Eros to Thanatos, and in a paradoxical way the death scenes seem to be the highlights, written with great beauty, sensuality, and drama. In these episodes Eline Boisen spells out what she wants to say with the memoirs in general: that human life takes place on the route between Heaven and Hell. There are two types of death scene: the terrible death, at which the road seems to lead straight to Hell, and the fine, sublime death, at which Heaven is open. In this, Eline Boisen is drawing on an old popular tradition that says the deathbed is where the individual is most aware of his or her self, and where our true nature can be seen. In the memoirs we can see, as it were, into Heaven when the gentle, pious women die. They lead an obscure, miserable existence here on earth, but in death they blossom, with the rose as a condensed, tradition-bound symbol of love and womanliness.

Agnes Helweg died in childbirth at the age of thirty-six; Eline was at her bedside and, incidentally, had to send her husband out of the room as he was disturbing the dying woman. Eline writes:

“She lay there lovely as a rose in fullest bloom, and I could not believe that death should be so close.”

Paradoxically, the dying woman seems more alive than the living, a feature that recurs in the description of her sister Ida’s funeral, at which the coffin is left open for as long as possible:

“A lovely rose lay on her breast – and her features were so gentle, so calm and peaceful that everyone had wanted to keep the coffin open to the last. – It was dreadfully cold, this March – and it appeared to me all the time that she must feel it over there in the chill grave – indeed – I even worried that she might possibly have been buried alive – so lovely as she was to the last.”

The Entrusted Talents

Like the revivalist movements of the common people, Eline Boisen questioned the theologians’ monopoly on interpretation of the Bible. And like the ‘true believers’, she read the Bible and found her answers; she paid particular attention to the parable of the talents. At first she was hesitant, “but the thought that perhaps I was like the servant who buried his master’s talents in the ground, afraid that he might lose them – and who by so doing was deserving of being cast into outer darkness – led me in a direction that did not make me happy – harried Boisen – without being of much benefit.” She gradually saw it as her right, in fact her duty, to speak her mind. Her intellectual talents were the specific gift given to her by the Lord, just as Boisen had been given a talent for preaching.

But she had constant scruples over whether she ought to fight to speak her mind when Boisen required her to submit to him: “Yes, here we have these 2 awful things right opposite one another – the woman must call her husband ‘Lord’ – and yet later ‘Whosoever loveth any human being more than our Lord – is not worthy of Him’. This is the mystery on which I have pondered ever since – but which will probably not be solved before the Lord releases me from this world.”

She could not be like Agnes Helweg and settle for silence, for being part of an unofficial tradition. Her knowledge had to be put into words, and she battled hard to make Boisen listen.

Paradoxically, her ideal set-up was nonetheless that of the patriarchal family, in which the man was the head of the family, and she considered it a great misfortune that she disagreed with her husband. In a way, it went against the natural order of things. She felt thrust out of a God-created order because her husband was closer to following the Devil in his religious and political commitment.

In their day-to-day life she, and not Boisen, was the head of the family; while Boisen had his ‘head in the clouds’, she endeavoured to the best of her ability to keep all the pieces together. Periodically, she supervised the running of the rectory, hired the curate, distributed poor relief, managed moving house many times, and took over the family’s keys when their finances had reached rock bottom. In other words, circumstances also forced her to consider her position as wife and to fight for her right to be an independently thinking human being.

The Swedish writer Sophie Sager, who was twelve years Boisen’s junior, went a step further and fought the cause of womankind; but first she had to do battle in the law courts. Eline Boisen’s campaign to be allowed to speak her mind was so hard-fought that she could give her husband no quarter: her position was one of total confrontation. For his part, he fought for freedom and equality for the common people, but demanded total submission from his wife at home. Bitterness eventually caused Eline Boisen almost to lose her mind. But notwithstanding the pressure she might feel coming from all sides, she wrote undauntedly to the last – her memoirs were intended as a plea at God’s court of justice – about the extent of the Devil’s power in the world.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch