No woman and no deity in the Middle Ages attracted the poets like the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ.

It is, however, hard to read what the poets write about Mary; we are inhibited by prejudices that block our understanding of what the texts are actually saying. Protestants dislike her because she is attributed divinity. Male chauvinists dislike her because she is a woman. Feminists dislike her because she is a woman in a way of which they disapprove. Nationalists dislike her because she represents an alien element in terms of creed and idiom. Marxists dislike her because they do not see her (in the North) as a figure of the people.

The following section on Danish medieval Marian writings will attempt to pass over these prejudices.

Marian literature is bound up with popular devotion to the Virgin Mother and Mariological theology, the latter usually following on from the former. Mary features in the New Testament, the most comprehensive and individualised account being in the Gospel According to Saint Luke. Mariological theology is based in this text, but often develops into interpretations that go beyond the direct biblical source.

The first important step towards a doctrine of Mariology was the decision taken at the Council of Ephesus in AD 431 that Mary was not only the mother of the man Jesus, but also of the divine Jesus. She was Dei genitrix, Mother of God, explained the theologians, due to her physical and mental purity. This in turn led to the dogma of Mary’s ‘perpetual virginity’, that is, that she was a virgin both before and after giving birth to Jesus. Mary became Virgo virginum, Virgin of Virgins. The doctrine of her ‘immaculate conception’ – the belief that Mary was born untainted by original sin, meaning that she had no predisposition to sin and no desire for sin – was not adopted until 1854.

Perceived as the Mother of God, and considered to be spotless, Mary became Mediatrix, mediator in the process of human salvation. This mediation took two forms: mediating, as it were, God to humankind by giving birth to Him, and mediating humankind to God by interceding on our behalf. The last major Mariological step was the Assumption, the belief that after her death Mary was taken up body and soul into heaven. This belief, however, first became a dogma of the Roman Catholic Church in 1950. In the Middle Ages, opinions differed on the issue of whether or not Mary had actually died before she was assumed into heaven. This is still an open question in Catholic theology. Nonetheless, this doctrine afforded Mary special status, given that other redeemed humans are only united in body and soul on Judgement Day.

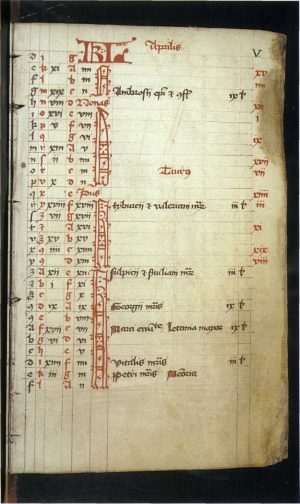

Influenced by the Eastern Catholic Church, the role of devotion to the Virgin Mary expanded in the Latin Western Catholic Church, and a number of feast days were held in her honour: Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 2 February, the Annunciation of our Lord to the Blessed Virgin on 25 March, the Assumption of Mary on 15 August, and the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin on 8 September. At the same time, various festivals within the popular tradition paid homage to Mary, including fertility festivals, and she often replaced pagan goddesses of fertility. It should be noted that Christmas day, the nativity of Jesus, is the mass of Christ and not a Marian feast day.

Lyrical Marian Poetry

Marian poetry written in Latin was extensive in terms of quantity, and extremely varied in terms of quality. Nonetheless, a number of central themes can be identified, such as: praise (Ave Maria poetry), which was often linked with prayers to Mary; poems about the sorrows of the Virgin Mary (Stabat Mater being the most famous example); and poems about the joys of the Virgin Mary (Gaude Maria, i.e. Rejoice, Mary).

A particular Virgin Mary style gradually evolved. One element of this technique was the listing of her epithets, such as Sun, Morning Star, Rose, Lily and Queen of Heaven. A specific Virgin Mary symbolism also evolved, in which elements from nature or from the Old Testament explained challenging aspects of Mariology. For example, the virgin birth was explained thus: just like the sun penetrates glass without breaking it, so did Mary become pregnant without the loss of her virginity.

Marian poetry in the Greek Catholic Church tradition can be traced to the sixth century. It flourished in the ninth century and was taken on by the Roman Catholic Church, where it culminated c. 1100-c. 1400. In the Late Middle Ages, Marian poetry adopted elements from French troubadour poetry (love poetry).

Marian poetry was initially written in the international language of religion, Latin, and might later have been translated. Original poetry was also written, in many genres and in the ‘vernacular’.

Lyrical, epic, and dramatic Marian poetry is found throughout the Nordic area. There are approximately fifty extant Marian texts in the Norse language, but they have not yet been the subject of comprehensive study. Some of these Norse Marian poems might have been written in Norwegian monasteries. In Sweden, poems to the Virgin Mother were written in Latin and in Swedish. Swedish-language Marian poetry exercised influence on its Danish counterpart through, in particular, the Birgittine order. The Swedish poems included, for example, “Vår Frus pina” (Our Lady of Sorrows) and – in various versions – a long poem about “Marias sju fröjder” (The Seven Joys of the Virgin Mary), one version of which is included in the wide-ranging and rhyming devotional book Siælinna thröst (Solace for the Soul). The oldest written version of the hymn “Den signade dag” (The Blessed Day) is Swedish and has strong Marian elements.

Marian poetic work in Denmark comprises Latin poems written by Danes as well as original and translated poems in the Danish language.

Two Latin sequences (hymns following the Alleluia of the Gradual), “Missus Gabriel” and “Stella solem”, were formerly attributed to Bishop Anders Sunesen (1167-1228), but recent research has shown that they cannot have been from his pen. A long poem of 150 double stanzas written in Latin, “Salutacio beate Marie”, has been attributed with reasonable certainty to the Roskilde priest Jacobus de Dacia, who died in the late 1300s.

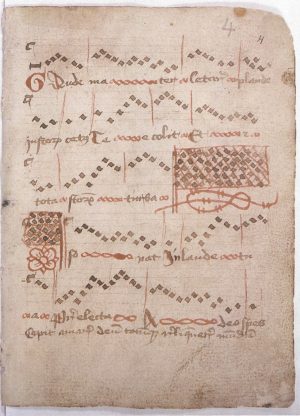

Extant Marian poetry penned in Danish comprises twenty-two poems. Some of these poems were written by named male authors. Per Ræv Lille wrote five Danish Marian poems, all found in a manuscript from c. 1470 titled En Klosterbog (A Monastic Book). Some of the poems were set to music. Per Ræv is considered to be the leading Danish Marian poet.

Herr Michael, a priest in Odense, wrote a Marian poem as an introduction to his book on the meditation of the rosary. Poul Helgesen wrote a number of Marian poems during the period of ecclesiastical reform, in one of which he expresses anger that it was no longer permissible to worship the Virgin Mary.

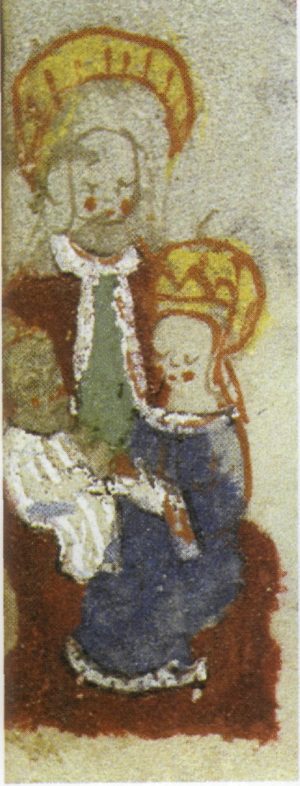

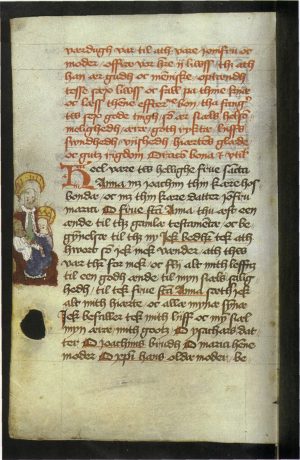

The other extant Danish Marian poems are all in prayer books. Approximately thirty Danish prayer books have survived from the Late Middle Ages. Together they contain about 1100 prayers, of which a few are written in verse. Following the European tradition, the prayer books are illustrated. The prayers have been published by Karl Martin Nielsen in Middelalderens danske bønnebøger I-V (1946-1982; Danish Prayer Books of the Middle Ages).

‘Marian songs’ is an umbrella term for all Marian poetic work that can be sung, including poetry that has not been, but could be, set to music.

The owners of the prayer books were all women. They were also the originators of the books – they saw to it that the books were written in the first place. These women were noblewomen of high rank with connections to the monastic milieu. The prayers are often translations from Latin, German or Swedish; some, however, must originally have been written in the vernacular. The writers or translators were monks and nuns. It is here important to point out that the writers and translators of the Marian poems in the prayer books might well have been women. It is of these Marian poems that the following will treat.

Marian Poetry in Prayer Books

The most thorough study of Danish Marian poetry is Ernst Frandsen’s 1926 doctoral thesis Mariaviserne (Marian Songs). This is still the standard work on the subject, containing pioneering research results and information. However, it is coloured by Ernst Frandsen’s general reservations about the subject, which stem from his national, Protestant and gender-conditioned prejudices. His central view is that the “strange un-Danish material” did not really ignite the poet-pens of Denmark, and that even Per Ræv merely represents “imitator work”.

Ernst Frandsen is right in his analysis that the Danish Marian poetry was not of the same original and international calibre as the Danish folksongs. On the other hand, if the Danish contributions to the genre are viewed as an inspiration and challenge to Danish thought, rather than as something ‘foreign’, then the perspective changes.

The Danish Marian songs in the prayer books are of three types: praise of the Virgin Mary, descriptions of Mary’s sorrows, and descriptions of Mary’s joys – all with built-in prayers.

Ave Maria

According to St Luke’s Gospel, when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to Mary he greeted her thus: “Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee” (Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum). When Mary later visited Elisabeth, she was received with the words: “Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb” (benedicta tu in mulieribus et benedictus fructus ventris tui). The Latin prayer Ave Maria, known around the world, originally consisted solely of these two greetings. The text can be traced back to the ninth-century Eastern Catholic Church. It became widely known throughout Europe in the eleventh century, and at the end of the twelfth century it was officially included in Church prayers. Franciscan and Dominican monks helped spread the prayer to the common people. The individual words – or some of them – could be learnt by people who had no knowledge of Latin. Eventually, a prayer addressed directly to Mary was added (although it first became an official prayer in 1568), and the prayer in its entirety became: “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou amongst women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen.” (Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum. Benedicta tu in mulieribus, et benedictus fructus ventris tui, Jesus. Sancta Maria, Mater Dei, ora pro nobis peccatoribus, nunc et in hora mortis nostrae. Amen.)

The lines in Ave Maria each hold far-reaching perspectives. Gabriel’s “full of grace” could be interpreted as meaning that Mary was not full of anything other than grace, that is, that she was without sin. This sinlessness is the premise for the notion that Mary has vanquished death and has the power to intercede on behalf of the dying. Ave Maria remains the most widespread prayer in the Catholic world.

There are other Latin prayers in praise of the Virgin Mary; for example, Ave regina (Hail Queen of Heaven) and Ave maris stella (Hail, Star of the Sea).

Of the Danish Marian songs in the prayer books, three are quite clearly prayers of praise, and two are partially so, but it has not been possible to establish any of the sources. They might well be original works. The following citations are in a modernised orthography.

Hil dig, Maria, den skinnende lilje,

du fødte din signede søn med vilje,

med de dråber, Gud selv dide,

frels min sjæl fra helvedes kvide.

(Hail Mary, the shining lily,

you willingly bore your blessed son,

with the drops God Himself did suckle,

save my soul from the torments of hell.)

(In the original Danish text “dråber” – drops – were “taaræ” which could mean drops or tears, but the context indicates the former.)

This rhymed (in the Danish) prayer, which was also set to music, is extant in three places in Danish prayer books. The version cited here is almost perfect as regards rhyme and rhythm, which was not the general rule for Danish medieval poetry. We have no information about this prayer, but as it is cited in three different places it must have been widely-known.

The poem is good, not merely on account of rhyme and rhythm, but because it is both simple and varied on every level. Mary is described with one of her familiar epithets: lily. This indicates beauty and purity, here reinforced by the adjective “skinnende” (shining/bright). The Danish “lilje“ (lily) rhymes with “vilje” (will), implying that Mary is not merely a lovely and passive mortal frame, but that she has become mother to Jesus by conscious choice. This corresponds to the Mary of St Luke’s Gospel, a role which has sometimes been interpreted as that of the world’s first Christian, because she is the first person to hear about and to acknowledge Christ. This entire religious perspective has been summed up in the little Danish verse by means of the “lilje-vilje” rhyme, which is phonetically correct

The poem makes another key point: “med de draaber, Gud selv dide” (with the drops, God Himself did suckle). This is an image of the fundamental mother-child situation, breast-feeding. At the same time, the writer has furnished the action with its divine dimension by replacing the infant Jesus suckling at his mother’s breast with “God Himself”. Moreover, to these drops is attributed the power to save the soul of the first-person narrator.

In her book Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary (1976), the British scholar Marina Warner devotes a whole chapter to “The Milk of Paradise” and makes an interesting comment that milk and tears were considered the only acceptable fluid emanating from the female body.

The poem “Hil dig, Maria, havsens stjerne” (Hail, Mary, Star of the Sea) has five stanzas. Ernst Frandsen is not impressed. He writes of the author: “His poetic ability is poor, it is restricted to being able to rhyme. And he is not in control of this ability, rather it is the rhyme that controls him.”

A positive view of the writer’s proficiency in rhyme would, however, note that here is another Danish author who has a good grip on rhyme and rhythm. The poem as a whole is not particularly accomplished, but some of the wording is noteworthy – for example, in the third stanza:

Du er oprunden af Davids rod,

aldrig fødes sådan imod.

Jeg kan det prøve med selver mig,

ærligste blomster fødes af dig.

(You spring from the Root of David

never will be born such to compare.

I can give proof of this myself,

most upright flowers are born of you.)

In the context, this stanza must be addressing Jesus. The second line means: never will anyone be born who can be held up against you, that is, compared with you. In the next two lines, the ‘I’ enters into a comparison with Jesus and acknowledges that Jesus is the greater. A strange image is applied: the most upright (that is, those that are most worthy) are born of you. What is meant by giving birth to flowers, and what does it mean that Jesus gives birth? The intention might be to give us pause for the thought that Jesus’ works are the greatest, but it is rather odd to associate actions with flowers, and Jesus with someone who gives birth. It may be that imagery usually applied to Jesus’ mother is here being applied to Jesus himself. The metaphors thereby highlight the overall picture presented in the song: that sometimes the first-person narrator sees Mary and her son as one.

At other points in the text they are clearly separated. The epithet “Star of the Sea” is plainly Mary. The Latin “stella maris” is quite correctly translated into the Danish “havsens stjerne”. The origin of this epithet is unclear, but it led to Mary being the protector of mariners; and therefore she was also called, as in the fourth stanza of the Danish text, a “guiding star”. In fact, the ‘star of the sea’ was Venus, the first star to been seen in the evening and the last to fade in the morning. There is thus a connection between the chosen epithet and the narrator’s wish to follow Mary.

The first-person narrator has achieved a degree of individuality in this text, not merely a stylistic ‘I’, but a human being able to choose a route through life:

Gud haver mig givet vid og skel,

giv mig dem at styre vel.

(God has given me wits and discernment,

may I handle them well.)

In this figurative steering situation, the narrator needs the mariners’ guiding star: Mary.

“Hil dig, Maria, verdens trøst” (Hail, Mary, Comforter of the World) is plain and simple when presenting the narrator:

Jeg er det menneske, som brødelig står,

hver dag jeg på jorden går.

(I am the person who, full of guilt,

walks the earth every day.)

The poem in general is very straightforward, with no great range as regards content or artistic ambition. It is based on the contrast between the first-person and Mary. The main point of interest in the poem is the fine choice of Danish epithets for Mary: verdens trøst (lit.: comfort of the world), himmerigs dronning (Queen of Heaven), smukkeste spejl (lit.: most beautiful mirror), væne rosens blomster (lit.: bloom of the fair rose), syndemænds lægedom (lit.: healing power over sinful men), moder uden mand (lit.: mother without mate).

The first line of “Hil dig Maria, fuld med nåde” (Hail Mary, full of grace) is a direct translation of “Ave Maria, gratia plena”. The rest of the poem deals with Mary’s sorrows and will be looked at later in that context.

“O Maria, jomfru fin” (O most gracious Virgin Mary) addresses both Mary and her mother Anne. The poem is distinctive in its comparatively forceful depiction of the devil and torments:

I helvede er redt med ild og kuld,

og sjælen er med sorger fuld.

(Hell is set with fire and ice,

and the soul is full of sorrows.)

Mater Dolorosa

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Franciscan and Dominican monks spread the Marian devotions of the seven sorrows and seven joys, subjects to which ordinary people could immediately relate. In the fourteenth century, when plague wiped out one third of the population of Europe, everyone could identify with Mary as mater dolorosa, the sorrowful mother.

The best stanzas of “O du overflydende kilde” (O Thou Overflowing Fount), a Danish poem written in couplet form, give a clear-cut and graceful depiction of the grief endured by the Virgin Mary over the death of her son:

O du overflydende kilde,

hvorfor er du nu så udflydende vilde?

O du vise mester over alle mennesker på jorden

hvorfor er du nu så tiende vorden?

O du klare skinnende sol,

over dig går så mørkt et mulm.

(O thou overflowing fount,

why art thou so wildly surging?

O thou wise master over all people on earth

why art thou now become so silent?

O thou bright shining sun

such darkness has come over thee.)

This Pietà in words is shaped by the contrast between the living and the dead son.

The best-known poem about the suffering of Mary is “Stabat Mater”, attributed to the Franciscan Jacopone da Todi (c.1230-1306), a work of passion and elegance in form and content alike. The poem falls into two parts: the first meditates on the sorrows of the Virgin Mary in her station at the Cross; the second is the first-person narrator’s prayer to Mary to be allowed to partake of her pain and to be granted her intercession on the day of judgement.

The Latin text is consummate in rhyme and rhythm, and full of stylistic niceties. The rhyme links the three-lined stanzas together two-by-two (thus, the first and second lines rhyme, as do the fourth and fifth, while the third line rhymes with the sixth line, and so on).

The Danish Catholic author and priest Peter Schindler (1892-1967) has commented that the Latin rhyme sounds like “deep death knells”.

Stabat mater dolorosa

Juxta crucem lacrimosa,

Dum pendebat filius.

Cuius animam gementem,

Contristatem et dolentem,

Pertransivit gladius.

“Stabat Mater” is found in a Danish prose version in Anna Brades bønnebog (Anne Brade’s Prayer Book), and in a Danish verse version in Marine Jespersdatters bønnebog (Marine Jesperdatter’s Prayer Book). The first stanzas in the Danish verse translation read thus:

Hos korsets træ

med sorg og ve

stod Kristi moder

med grådens floder,

hendes søn på korset hængte.

Af suk og gråd

som før var spå’t

med stor ufryd

stak drøvelsens spyd

hendes hjerte det da trængte.

This text is not elegant and perfectly-formed like the Latin, but it is good Danish and the rhyme and rhythm are correct; in fact, there is more rhyme than in the original, because each stanza now has five rather than three lines. Not just the style, but also the content has been muted in translation. The first-person is not so ardently passionate; for example, there is none of the Latin “cruce hac inebriari” (inebriated by the cross). The objective of the first-person speaker is primarily to show empathy with Mary’s suffering. In the original poem, Mary is both the gentle mother and the stern blessed virgin of all virgins; in the Danish text she is gentle throughout. All the toning down is elegantly demonstrated in the following stanza, which also includes an original metaphor not found in the Latin, that of “milde rose” (gentle rose):

O milde ros’

lad mig stå hos

og bære med dig

af drøvelse slig,

som da dit hjerte måtte gæste.

The Danish version might not have the stylistic star turns of the Latin, but the translator has nonetheless spared no pains concerning the purely phonetic aspect of the matter; for example, there is a clearly discernible artistic use of the ‘ø’ and ‘m’ sounds in the final stanza. The author who rendered this major international poem into Danish can be proud of the result:

O milde mø,

når jeg skal dø,

gak for din søn

med moderlig bøn

og frels min sjæl af våde. Amen.

“Hil dig Maria, fuld med nåde” (Hail Mary, full of grace) follows the route of Mary’s Passion, that is, the Sorrows she encountered during her life. The poem opens, as mentioned earlier, with Gabriel’s salutation, and embraces the eulogistic tradition in that most of the stanzas conclude with an Ave Maria. The text is structured on a steadfast pattern: first, a depiction of one of Mary’s Sorrows; next, the first-person speaker makes a prayer connected to this Sorrow. The fourth stanza thus states (the Old Danish version has full rhymes, as, for example, in “twongen-fongen”):

Maria, du var af sorgen tvungen

den tid, du spurgte, din søn var fangen,

jøderne bandt ham med migel gere

så ledte de ham for dommer fire.

Fordi han tålte så uskildelig

Frels min sjæl evindelig. Amen. Ave Maria.

(Mary, you were by sorrow pressed

that time, you learnt your son was captive,

the Jews bound him with many cords

then led him before four judges.

Because he suffered so unjustly

Redeem my soul for evermore. Amen. Ave Maria.)

A particular feature of this Marian poem is its folksong turns of phrase, which can clearly be heard in the cited stanza as well as in the final stanza’s depiction of Mary:

Din’ kinder blege, din’ øjen var røde

aldrig så nogen tåle sådan møde.

(Your cheeks pale, your eyes were red

no one was ever seen to bear such agony.)

Rejoice, Mary

The Danish prayer book is not only the agency for the Ave Maria and Mater Dolorosa tradition; it also contains poems about the Virgin Mary’s joys.

“Gaude virgo mater Christi” (Rejoice, Virgin Mother of Christ) is a lyric Latin tradition that can be traced far back in time and which has many variants. The “Rejoice, Mary” poems were presumably originally written (and sung) for the Mary festivals. Thus, in the ninth century at the famous Abbey of St Gall in modern Switzerland, the monk Notker Balbulus (c.840- 912) wrote a “Moderhymne” (Hymn to the Mother) for the festival of Christmas, 1 January. This should not be confused with the Christmas song for Jesus’ birthday, 25 December, which also treats of joy: “Dies es laetitiae” (This Day is a Joyful Day). The ‘rejoice’ poetry gradually evolved into texts dealing with either Mary’s celestial or her earthly joys. The latter tradition generally specified five or seven joys.

“Glæd dig Maria, Guds moder, og fryd dig” (Rejoice, Mary, Mother of God, and Be Gladdened) is the longest and most discussed of the Danish joy-poems. The poem is similar to four extant Swedish and one extant German poem, but has differences that are too marked for it to have been a direct translation.

At no point do any of the studies of the Danish poem mention that the first-person narrator is a woman. This is nonetheless apparent in three of the poem’s petitions: “og hans tro tjenestekvinde dø” (fourth joy; and die His faithful servant woman), “alsomhelst vil jeg din tjenestekvinde være” (sixth joy; most of all I want to be your servant woman), and “giv mig min jomfrudom således at leve / at jeg må være uden din vrede” (seventh joy; give me my virginity thus to live / that I may be without your wrath). The latter petition could suggest that the woman speaking is young, and that it demands an effort on her part to live in a state of virginity. Of the sources, interestingly, the German text has no indication of a female narrator and only one of the Swedish poems has a female first-person voice (but this is only heard once, in contrast to the three Danish occurrences).

A female first-person voice does not necessarily signify a female writer/adapter; but the writer might have been a woman. The user, on the other hand, must have been a woman, given that it is unlikely that anyone would have written a prayer with a female first-person voice to be used by a monk or a nobleman.

In order to understand “Rejoice, Mary”, it is necessary to appreciate that the poem is written from the perspective of an extolling and worshipping woman who wants to follow Mary in her role of Virgin.

The seven joys addressed in the poem are: the Annunciation, the Visitation, the Nativity of Jesus, the Adoration of the Magi, the Passover pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the Finding in the Temple, the Assumption of Mary. Ernst Frandsen is displeased with the fifth and sixth joys, which in his opinion should have been the Resurrection of Christ and the Ascension of Christ to Heaven. The writer might have avoided these two joys, speculates Frandsen, “because they require greater religious energy than those he puts in their place”. Awareness that the poem’s entire energy field is fuelled by a personal struggle with the issue of virginity, however, leads to a different conclusion. By way of illustration, the sixth joy will be examined, here quoted in modernised orthography:

Glæd dig, Maria, den signede daggry,

den sjette glæde kom dig til hand,

så at ingen hende fuldsige kan,

der du din signede søn igenfandt.

O du søde jomfru rene,

i tre dage havde du ham tabt

og tålte for ham men.

Alsomhelst vil jeg din tjenestekvinde være,

fordi at din renhed monne den enhjørning forvinde,

du haver af den løve et lam gjort

og tæmmet den vilde ørn, som vi have hørt,

du haver bundet den stærke Samson

og forvundet den vise Salomon,

du haver den vilde pelikan fanget,

og salamander er af ilden til dig gangen;

du haver og spæget den vilde panter

og tvunget den store elefant,

af dig blev den gamle Fønix ung,

der Guds søn sprang det høje spring

af det høje himmerige

og hid ned til jorderige,

der Guds søn lod sig føde af dig.

For din sjette glæde beder jeg dig,

vend din grundløse miskund til mig.

Maria trøst mig usle menneske,

og hør min hjertens røst,

tag min mening for alles tale

giv alle bedrøvede hjerter husvalelse,

hver efter som ham trænger nød

hjælper ikke du, da bliver jeg død.

Amen. Salve regina misericordie.

(Rejoice, Mary, the blessed dawn,

the sixth joy came to you

such that no one may fully state it,

there your blessed son you found again.

O you sweet Virgin pure,

for three days you had lost him

and suffered for him ill.

Above all I would your servant woman be,

because your purity would the unicorn appease,

of the lion you have made a lamb

and tamed the wild eagle, as we have heard,

you have bound the strong Samson

and defeated the wise Salomon,

you have captured the wild pelican,

and salamander has from the fire walked to you;

you have also curbed the wild panther

and subjugated the huge elephant,

by you the old Phoenix became young,

in you God’s son took the mighty leapfrom the high heaven

and down to the earth,

in you God’s son was born of you.

For the sixth joy I pray you,

turn your bottomless mercy to me.

Mary comfort me wretched human,

and hear the voice of my heart,

take my words for the speech of all

give all distressed hearts solace,

each according to their want

if you do not help, so am I dead.

Amen. Salve regina misericordie.)

The sixth joy is based on St Luke’s account of an episode when twelve-year-old Jesus was visiting Jerusalem and disappeared for three days because he was in discussion with the elders in the temple. The core point in this text is the divine child’s conflict between celestial and earthly obedience.

“How is it that ye sought me? wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?” says Jesus. His parents do not understand him, but Mary “kept all these sayings in her heart”, and Jesus “increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man” (St Luke 2:41-52). This episode features in a number of places in Danish medieval literature. In the widely-read book Jesu barndomsbog (The Childhood of Jesus) the conflict is more clearly depicted, and a balance is achieved. Joseph and Mary understand that Jesus is God’s son, and he for his part “practised mortality”, that is, he learnt to assume the responsibilities of a mortal human being. The subject is also addressed in the folksong “Jesus og jomfru Maria” (Jesus and the Virgin Mary). Mary finds Jesus in a herb garden:

‘Hør du, Jesus, kære sønnen min,

hvi gjorde du mig den angst og kvide?’

Jesus han svarede moder sin:

‘Skal jeg ikke luge blomsterne mine?

Jeg luger de store, jeg luger de små,

dem, torne bær, kaster jeg frå.’

(‘Listen, Jesus, dear son of mine,

why did you cause me that anxiety and distress?’

Jesus answered his mother:

‘Am I not to weed my flowers?

I weed the big, I weed the small,

those bearing thorns I throw away.’

The point of the prayer book treatment of the story of Jesus’ disappearance is that Mary not only finds but also regains her divine child. The reason that she has the power, that she can, so to speak, compete with God for the child, is – according to “Rejoice, Mary” – her virginity. That is the source of her power.

This episode has been depicted in a short story by Selma Lagerlöf, “I templet” (1904; In the Temple, from Kristuslegender,eng. tr. Christ Legends).

“‘Why weepest thou? I came to thee as soon as I heard thy voice.’

‘Should I not weep?’ said the mother. ‘I believed that thou wert lost to me.’

They went out from the city and darkness came on, and all the while the mother wept. ‘Why weepest thou?’ asked the child. ‘I did not know that the day was spent. I thought it was still morning, and I came to thee as soon as I heard thy voice.’ ‘Should I not weep?’ said the mother. ‘I have sought for thee all day long. I believed that thou wert lost to me.’

They walked the whole night, and the mother wept all the while. When day began to dawn, the child said: ‘Why dost thou weep? I have not sought mine own glory, but God has let me perform miracles because He wanted to help the three poor creatures. As soon as I heard thy voice, I came to thee.’

‘My son,’ replied the mother. ‘I weep because thou art none the less lost to me. Thou wilt never more belong to me. Henceforth thy life ambition shall be righteousness; thy longing, Paradise; and thy love shall embrace all the poor human beings who people this earth.’”

All the symbols that the writer can find in medieval nature study and the Old Testament serve the one purpose of demonstrating Mary’s extraordinary power. She can capture the unicorn; she can tame the panther, the elephant, and wise Solomon. She can make the salamander, which can only be captured by fire, leap from God’s flames to her flames; she can make the old phoenix young again. All the elements she tames are symbols for Jesus; the text takes on an erotic twist because the symbols sometimes signify God, sometimes Jesus, so that at times both a child and a lover are captured by her virgin-power.

The final six lines show the Danish adapter’s personal gravity in the appropriation and dissemination of Mary’s sixth joy. The lines are all additions, with neither German nor Swedish parallels; straightforward lines without stylistic refinements – speaking purely and simply to Mary. It really sounds like someone speaking from the heart, humble and sincere – and without forgetting the others.

The Danish text is also on its own when it comes to rounding off the poem. It is the only one in which we find the petition “giv mig min jomfrudom således at leve […]” (give me my virginity thus to live). This supports the impression that it is a virgin talking to Mary.

“Rejoice, Mary, Mother of Christ” consists of seven reasonably regular stanzas. It describes the usual Mary joys. Of the Virgin Birth, the poem has this distinctive image:

Som roser og liljer udspredt giver lugt af sig,

så fødte du Jesus, sand mand af dig.

(As roses and lilies unfolded give off their scent

thus you gave birth to Jesus, the true man of you.)

The line of thought behind this metaphor is that Mary gives birth completely effortlessly.

This circumstance was often highlighted in the Middle Ages, one of the standard metaphors being: like the stars give off light without losing their power, thus Mary gave birth to Jesus. According to Ernst Frandsen, the metaphor in the Danish text was purely Danish; Per Ræv also uses it.

From a modern vantage point it is easy to see the repression of bodily function in these images: everything that could suggest a woman’s labour and pain in the act of giving birth has been removed.

Medieval painted renditions of the Virgin Birth often show Mary standing up or squatting. These paintings prompt another interpretation that might also apply to the textual metaphors: that Mary represents a tradition from the birthing position of the past; she gives birth standing up and effortlessly. Two entirely different analyses of childbirth can thus be found in the same image.

The third Danish joy-poem, “Glæd dig, Guds moder, jomfru Maria, fuld med ære” (Rejoice, Mother of God, Virgin Mary, full of glory), is not about the joys that came to Mary, but about the joy she represents. Consistent with the genre, the first-person voice asks to share in this “eternal joy”. The poem has a striking number of epithets for Mary: glædens dronning (Queen of joy), mildheds kilde (spring of gentleness), klar som skin (clear as light), sødheds gren (bough of sweetness), engles og hellige mænds fryd (delight of angels and holy men), jomfruers spejl (mirror of virgins). The latter title is, according to Ernst Frandsen, an original Danish construction. However, it also features in the title of the Danish translation of the life of Catherine of Siena in the Mariager Legende håndskrift (Mariager Legendary), compiled in the late fifteenth century.

Comparison with Per Ræv and Herr Michael

The Marian writings of Per Ræv and Herr Michael will not be examined in detail here, given that the principal topic is Marian works that might well have been written by women. Per Ræv and Herr Michael will serve to put the Mary of the prayer books into perspective.

Per Ræv’s Marian poems are all to be found in a late-fifteenth-century compilation manuscript, published in 1933 as En Klosterbog (A Monastic Book).

Per Ræv’s Marian songs are different from the others. They are amorous. The narrator is in love with Mary. Per Ræv has been called “Vor Frues troubadour” (Our Lady’s Troubadour), because he sings to Mary in the way that French troubadours sang to the married noblewomen they ‘courted’. Per Ræv’s Marian songs are probably original Danish works.

To compare Per Ræv’s writings with the prayer books, we can look at his Marian song “Gud faders magt kalder jeg oppå” (The power of God the Father I call upon). The poem has seventeen stanzas, all in the most delightful rhyme, and Per Ræv employs the same symbols from the Old Testament and nature study as were used by the author of “Glæd dig Maria, Guds moder, og fryd dig” (Rejoice, Mary, Mother of God, and be gladdened) – panther, unicorn, salamander, the phoenix bird and many others – but they are used in a different context. Per Ræv does not identify with Mary, and he does not try to understand her joys. He is fond of her and wants to describe her, as he says, “from head to foot and in between”. The result is a full-body portrait of a woman with yellow-blond hair, sparkling eyes, lily-white hands and feet, and a shapely figure:

Du er vel voksen smal omkring,

du lignes ved den alædleste ting,

som himmel og jord kan have,

det volder Gud fader han haver dig kær,

du fødte hans søn, både ren og skær,

alt af den helligånds nåde.

(You are comely of slender build,

you are compared with the most noble thing

that heaven and earth can hold,

that makes God the Father hold you dear,

you bore His son, both pure and tender,

all by the grace of the Holy Spirit.)

God held Mary “dear” in the prayer book text too, but there the argument is like that in St Luke’s Gospel: Mary’s soul was ready. To Per Ræv’s mind, the argument is that Mary was beautiful.

If the prayer book author is the virgin in Danish Marian lyrical writing, and Per Ræv is the amorist, then Herr Michael is the theologian.

He was a priest at Saint Albani Church in Odense. He wrote just one known Marian song, used as the introduction to his rhymed work on Jomfru Mariæ Rosenkrans (Rosary of the Virgin Mary), printed in 1515, and probably written in 1496.

“Min hu, min agt og alle minne sinde” (My mind, my intent and all my thoughts) is the title of Herr Michael’s Marian poem of twenty-one stanzas. The first two stanzas bear traits of troubadour lyricism: the first-person voice would value “a worthy woman”, but that is as far as the troubadour in Herr Michael goes. There is no yellow-blond hair, no lily-hands and slim waists, no roses and lilies, no unicorns or salamanders. All the metaphors are courtesy of the Old Testament: Aaron’s staff, the burning bush and numerous biblical personages. It is striking that the men, and especially the women, mentioned from the Old Testament have all killed an enemy: “Judith hun tog hans egen kniv/ hans hoved hug hun fra hans liv” (lit.: Judith took his own knife/ cutting his head from his torso) – “en kvinde med en mægtig sten/ knused hans hoved, gjorde hannum det mén” (lit.: a woman with a mighty stone/ crushed his head, did him that injury). All of this was designed to throw Mary into relief, for she has killed a greater foe:

Så lægger Maria djævlen øde,

dem, synden haver dræbt, rejser hun af døde.

(Then Mary lays the devil waste,

those killed by sin she raises from the dead.)

Herr Michael is, from a religious point of view, the most rigorous of the Danish Marian poets. He does not see Mary as the intermediary, but as the saviour.

In terms of the history of language, the Danish Marian songs are part of the enterprise defined by the philologist Paul Diderichsen as the shaping of a Danish literary language according to the Latin models. The lyrical Marian texts were attempting to shape Danish language in rhyme and rhythm, to develop the sense of a lyrical ‘I’ and to disseminate the special stylistic features, epithets and symbols of Marian writings. Unlike Ernst Frandsen, I think the enterprise succeeded well.

At the same time, the writers and translators of Marian songs had to introduce an international, but in the Nordic area completely new, theme: Mary. This was done in different ways. Mary of the prayer books, who might have been created by women, was the gentle and powerful virgin; Per Ræv’s Mary was the divinely beautiful woman; and Herr Michael’s Mary was the saviour.

Mary was introduced into Danish literature by women and men in the monastic and convent setting. She has come to stay, despite the changing times. “No image stood firm in human dreams as the Mother of God,” wrote Sophus Claussen in his famous poem “Atomernes Oprør” (1925; Revolt of the Atoms); it would seem he was right. From the Middle Ages onwards, there has not been a period, and hardly an author, in Danish literature that has not drawn in some way or other on the Marian tradition. Part of the personal aura of the central character in Kirsten Thorup’s Himmel og helvede (1982; Heaven and Hell), for example, comes from her name: Maria (Mary). If she had been called Suzanne she would have been a different character.

The Marian poems in the prayer books have here been looked at from the angle of textual analysis. This reading makes it probable that some of the writers were women. This study could be elaborated by means of a ‘repertoire’ examination of the manuscripts; that is, by examining who owned each individual prayer book, who initiated it, and who wrote in it. The latter study would require highly detailed examination of the extant manuscripts. Each manuscript could also be examined as a whole, affording an overview of the prose, the poetry, the annotations and the illustrations. Having thus studied the ‘repertoire’ of each manuscript, a picture would emerge of its overall setting. The publisher of Middelalderens danske bønnebøger (Danish Prayer Books of the Middle Ages) has provided a foundation for such ‘repertoire’ studies, but many issues are still to be addressed; for example, the identification of the individual scribes. Should this scrutiny of Danish prayer books be undertaken, the significance of noblewomen and nuns in the literary history of the Danish medieval period would most likely be corroborated and reinforced.

In terms of philosophy, the figure of Mary is one of the strongest exponents of the idea that beauty and virtue are linked. It is not possible to imagine an ugly Mary. “Beauty gives birth to virtue,” wrote an Italian Renaissance poet. This is a striking perspective vis-à-vis our own times, in which the beautiful and the good no longer go hand in hand. We have separated aesthetics and ethics.

The psychological perspective of the Mary figure is – apart from an astute article by Julia Kristeva – the least explored. There can be no doubt that Mary has made deep inroads into the western psyche, but there is a shortage of thorough studies into the ‘Madonna complex’.

The 1970s did indeed see studies of the Madonna/whore schism, but these studies only cover a single and very narrow view of the Mary figure. Moreover, as analyses they all suffer from the same shortcoming, in that they do not address the simultaneous schism in the male picture of God/Devil, God/Joseph, God/Jesus.

In terms of religion, Mary is an intermediate station. In relation to the mother and love goddesses of pre-Christian religion, which she replaces, she is a deity much reduced in force and influence. However, she plays an important role in relation to the Protestantism that followed on from Catholicism in the northern regions of Europe. After her, all deity of the female kind vanishes from Nordic religion. Mary stands on the threshold to a patriarchy that will compound its power.

Translated by Gaye Kynoch